Not just a bag of words, but a thing held by human hands.By Alexis C. Madrigal

BookTraces is a new project to track down the human markings in 19th-century books that, in the era of digitization, will (at best) end up in deep storage throughout the nation’s library system.

The books are “a massive, distributed archive of the history of reading, hidden in plain sight in the circulating collections,” the site argues. “Marginalia, inscriptions, photos, original manuscripts, letters, drawings, and many other unique pieces of historical data can be found in individual copies… Each book has to be opened and examined.”

While the implications of this research are large for librarians (more on that anon), for the lay person, there is a fascinating question at the heart of this project to find and preserve unique copies of old texts:

In the Kindle era, it seems pretty obvious. There is an implicit argument in the act of digitizing a book and removing it from the shelf: a book is its text. A book is a unique string of words, as good as its bits.

But printed books are also objects, manufactured objects, owned objects, objects that have been marked by pencils and time and coffee cups and the oils from our skin. “A book is more than a bag of words,” the project’s founder, University of Virginia’s Andrew Stauffer, told me. “These books as objects have a lot to tell us.”

Like what?

Each book-object has two primary categories of stories to tell. The first concerns the history of the book’s own reception. What annotations did people make on the text? What do their aftermarket markings tell us about how the book was read? How was it understood?

“In certain ways, a project like RapGenius is the modern day equivalent of what BookTraces might discover for the 19th century,” Stauffer said.

When I interviewed him earlier this year, RapGenius’ Ilan Zechory told me that he considers annotated-texts to be the way that documents should be experienced now. Instead of the fixity and narrowness we associate with print, the RapGenius vision is one in which all texts are surrounded by the ideas and people who inspired and commented on the work. The text is like a field of clover and the annotations are like bees, pollinating.

BookTraces, if it were widely deployed, could show that RapGenius has a textual precursor: the marks in books capture some of the ecosystem of ideas that surround all texts exchanged between people.

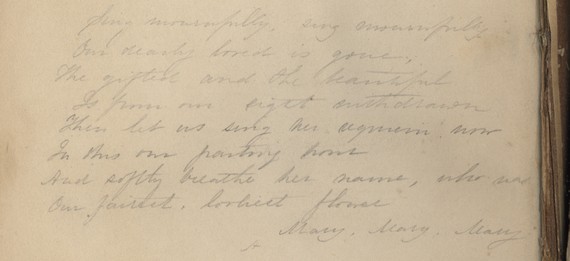

Stauffer gives a poignant example. A woman named Ellen received a book by the sentimental poet Felicia Hemans. Years later, her seven-year-old daughter died, and she adapted lines from Hemans to create a memorial inside the book. Mary, Mary, Mary.

Moved by this, Stauffer looked at another edition of Hemans in the UVA library and found a similar tribute to a lost child. “This really tells us something about how people were using Hemans and this book to refract their own grief,” he said.

But there’s a second kind of story that the books can tell, too: the history of reading in the 19th century.Each book-object contains pages of paper, which might have been prized—at any given moment—more as scrap paper for making a laundry list or doing longhand math than for its literary value. At the beginning of the century, Stauffer explained, paper was pretty expensive, as processes for turning wood pulp into clean sheets had not been developed. “The whole 19th-century is the story of paper getting cheaper,” he said. “It’s a little like digital access, the way bandwidth is getting better. There was just more and more paper available.”